Nissrine Fessikh

11-08-2021 6 min readThe next Chrome update that will change the rules of the web

Google Chrome is definitely abandoning Third-party cookies. If all goes according to plan, future updates to the world's most popular web browser will rewrite the rules of online advertising and make it much harder to track the web activity of billions of people. But it's not that simple. What seems like a big win for privacy may ultimately only serve to tighten Google's grip on the advertising industry and the Web as a whole.

Critics and regulators argue that the move risks putting small advertising companies out of business and could hurt websites that rely on advertising to make money. To most people, the change will be invisible, but behind the scenes, Google plans to put Chrome in control of part of the advertising process. To do this, it plans to use browser-based machine learning to record your browsing history and group people into groups alongside others with similar interests.

Google's plan to replace third-party cookies comes from its Privacy Sandbox, a set of proposals to improve online ads without wiping out the advertising industry. In addition to getting rid of third-party cookies, Privacy Sandbox also addresses issues such as ad fraud, reducing the number of CAPTCHAs people see, and introducing new ways for companies to measure the performance of their ads. Many critics of Google say that parts of the proposals are an improvement over the existing setup and are good for the Web.

Change is necessary. The online advertising industry is, to say the least, unwieldy. It includes billions of data points about all our lives that are automatically exchanged every second of every day. Such a substantial change to this system will impact many businesses, from brands advertising products and services online to the ad technology networks and news organizations that propel these ads to every corner of the Web.

Privacy Sandbox proposals are complicated and technical. Google is already testing some of them while others remain firmly in the development stage. Privacy Sandbox is documented online and Google has modified its plans based on feedback and counter-proposals from its rivals. But ultimately, when it comes to Chrome, everything is controlled by Google.

The removal of third-party cookies from Chrome, first announced in January 2020, is long overdue. When Google does remove them, it won't be the first, but its huge market share means it will have the biggest impact. Apple's Safari, the second-largest browser behind Chrome, limited cookie tracking in 2017. Mozilla's Firefox blocked third-party cookies in 2019 - the problem is so vast that the browser currently blocks ten billion trackers a day.

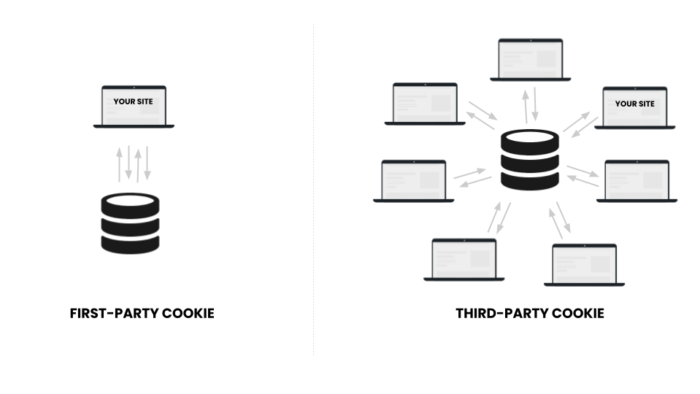

If you're using Chrome at the moment, the websites you visit, with a few exceptions, will add a third-party cookie to your device. These cookies - small snippets of code - are able to track your browsing history and display ads based on it. Third-party cookies send any data they collect to a different domain than the one you are currently on. Proprietary cookies, by contrast, send data back to the owners of the domain you are currently visiting.

Third-party cookies are the main reason why the shoes you looked at two weeks ago are still pestering you on the Web. All the data collected by third-party cookies are used to create user profiles, which can include your interests, things you buy, and online behaviors - this can be sent back to the troubled data brokers. "The intention was really to launch a certain set of proposals on how older technologies like third-party cookies, as well as others, can be replaced with privacy-preserving API alternatives," says Chetna Bindra, product manager in Google's ads business.

So what are the alternatives?

Google's plan is to target ads against people's general interests using an AI system called Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC). The machine learning system takes your web history, among other things, and puts you in a certain group based on your interests. Google has not yet defined what these groups will be, but they will include thousands of people with similar interests. Advertisers will then be able to place ads in front of people based on the group they are in. If Google's AI determines that you really like sneakers, for example, then you will be thrown into a group with other like-minded sneaker fans.

It all works in the same way that Netflix's algorithm determines what you would like to watch. In essence, your viewing history is similar, but not identical to many others. If Person A and Person B both like the same four horror movies, for example, there's a good chance that Person A likes a fifth horror movie that Person B just watched. Now expand that to cover billions of people.

Unlike third-party cookies, any data used to determine which group you enter will be processed in Chrome. Third-party cookies, on the other hand, are vaporized like confetti. Bindra says that despite this fundamental change in the way data is stored and processed, the system is 95% as effective at targeting ads as third-party cookies.

A potential problem with the machine learning system is what it can infer about people. While FLoC means that less personal data is sent to third parties, as with the current cookie configuration, there are concerns about how people will be grouped and whether the automated process that does so will discriminate against certain groups. If other browsers choose to adopt the machine learning configuration, Yahoo! Japan would be interested - they may be able to modify the grouping for their own use.

Don't miss any news, subscribe now!

Related articles

Publications recommandées